Since the Trump Administration unveiled its reciprocal tariff policy on April 2, headlines have focused on the wide range of rates applied to different countries. Now, President Trump and other government officials are beginning to pivot towards other areas of global trade friction to accomplish their goal of reducing trade deficits.

U.S. strategy appears to be shifting to the less obvious but often more harmful trade obstacles called non-tariff barriers. These NTB measures, including quotas, licensing requirements, product standards, digital taxes, and ownership restrictions, are significant obstacles to expanding U.S. exports across strategically important sectors such as agriculture, technology, media, and services.

While tariffs aim to reduce U.S. imports and raise revenue, challenging non-tariff barriers to trade aims to boost U.S. exports. If other countries remove these hidden restrictions, American companies can gain better access to international markets. Observers expect to accomplish NTB reform by negotiating them away in exchange for lower tariffs. However, breaking down NTBs will be complicated. The fact that the U.S. maintains its own trade barriers further complicates negotiations.

What Are NTBs And Why Do They Matter?

Non-tariff barriers are trade restrictions that don’t involve a tax. While countries often justify these measures on grounds of consumer safety, environmental protection, or national security, they can also protect domestic industries from foreign competition.

For U.S. exporters, non-tariff barriers implemented by critical trading partners such as the European Union, India, and China act as stealth roadblocks that limit market access. These restrictions can be more impactful than traditional tariffs in many sectors.

Europe’s Playbook: Protectionism Through Standards

In the past, U.S. policymakers have been critical of the European Union for using regulatory frameworks to achieve protectionist ends. For example, bans on hormone-treated beef and slow GMO approvals severely restrict U.S. meat and crop exports from entering the EU. Similarly, the EU’s Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act are thought to limit activity from dominant American technology platforms under the guise of privacy and competition. In addition, the EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which levies carbon fees on imports based on their emissions, reflects Europe’s more stringent climate policy and raises costs for U.S. manufacturers with fossil-heavy supply chains.

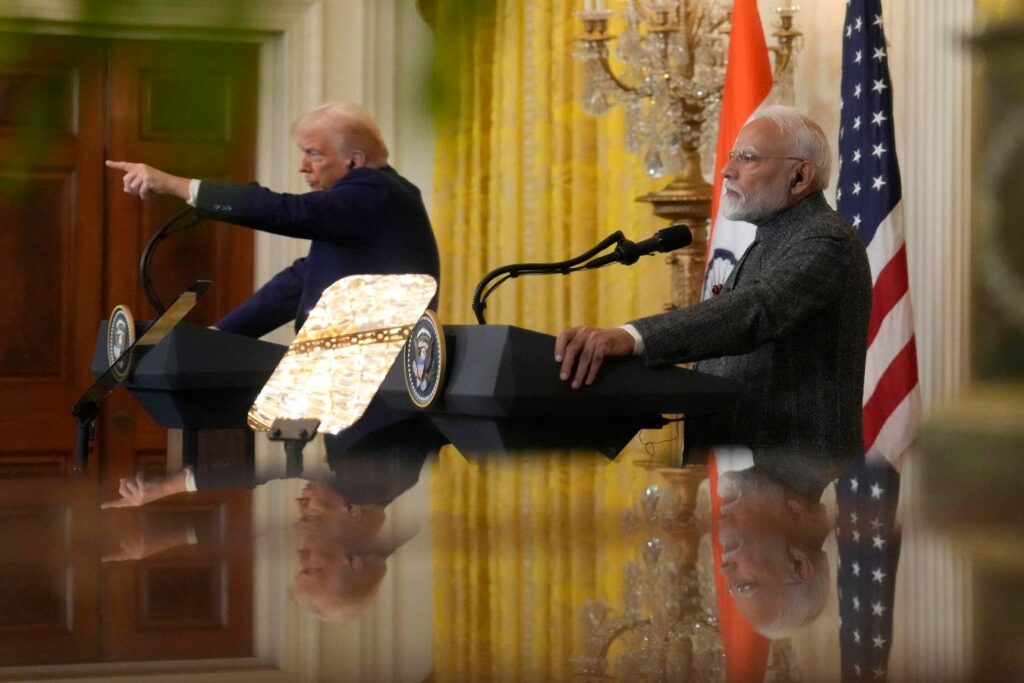

India and China: Guarding Markets With Data and Regulations

India’s NTBs are more direct. India’s import licensing requirements, foreign direct investment caps, and state-run trading monopolies control who can do business and under what terms. U.S. retail, insurance, and finance firms face legal ceilings on their market participation. For example, Walmart had to enter India through a joint venture and later shifted focus to wholesale operations instead of pursuing full-fledged retail stores. Another Indian NTB is that regulators increasingly require in-country testing and certification through its Quality Control Order regime, which causes delays and duplication of tests that raise costs and reduce competitiveness for U.S. exporters.

In China, the challenges are deeply strategic. Data localization laws prohibit U.S. cloud providers and platforms from freely operating. Also, despite commitments to open up, technology transfer requirements and joint venture mandates still effectively coerce U.S. companies into giving up intellectual property.

Furthermore, China restricts the import of many U.S.-grown foods through its slow and complex approval process for biotech crops, often citing health and safety concerns as justification. China uses these measures to protect domestic agriculture and control food supply chains to help achieve its broader strategy of ensuring food security and technological self-reliance. Even when international scientific consensus deems certain GMO products safe, China’s regulatory delays limit U.S. agricultural exports, creating a hidden non-tariff barrier that advantages Chinese farmers and biotechnology firms.

The U.S. Has Its Own NTBs

Complicating negotiations may be the fact that the U.S. maintains its own assortment of non-tariff barriers.

The Jones Act, for instance, requires goods shipped between U.S. ports be carried on U.S.-flagged vessels. This requirement raises shipping costs and limits foreign participation in domestic maritime commerce. Buy American rules embedded in federal procurement favor domestic manufacturers, sometimes at the expense of cost efficiency. Agriculture is protected via tariff-rate quotas that limit imports of sugar and dairy. Foreign ownership caps exist in critical sectors like telecom, aviation, and defense. All of these policies serve to protect U.S. jobs and national security. However, they also undermine American credibility when calling out similar behavior abroad.

Reform Is Hard—And Not Just Politically

Even if foreign governments are willing to reform their domestic NTB policies, the process would likely be very slow and politically difficult. Many NTBs would require a change in domestic laws tied to stated public goals, such as environmental protection, health safety, or cultural preservation. Yes, the NTBs restrict foreign imports, but they also serve a purpose for the domestic population.

In many cases, reform would require more than just policy changes. It would involve regulatory overhauls, new certification regimes, or multilateral agreement updates, which could take years to implement. According to Apollo Global Management, the average trade deal takes 18 months to negotiate and 45 months to become effective. Negotiating dozens of new agreements before the July 8 expiration of reciprocal tariff suspensions would be challenging.

A Complex Power Game

With respect to NTB reform, there is more at play than simply trying to change the rules to allow for more U.S. exports to other countries. Targeted non-tariff barrier reforms can help the U.S. achieve its geopolitical and national security goals by reshaping trade dependencies and institutionalizing alliances.

For example, part of an NTB deal with India could include shifting its oil imports from Russia to the United States. India accounts for roughly 40% of Russian oil exports, the loss of which would cost Russia an estimated $22 billion annually. Interrupting this flow could help Western efforts put additional financial pressure on Russia to help negotiate a settlement with its ongoing war with Ukraine.

By reducing non-tariff trade barriers and possibly negotiating down the level of reciprocal tariffs, the U.S. aims to advance its goal of improving exports, reduce its trade deficits, and improve its position from a national security perspective.

What’s At Stake

The stakes are high. Financial markets are banking on some sort of agreement that will avoid the imposition of the tariff rates announced by the Trump administration, currently on suspension until July 8. The success of potential agreements will depend on whether U.S. officials can make progress on the non-tariff trade barriers in the various countries. Failure to reach bilateral deals could mean the high tariff rates remain in place. This could put further pressure on stock and bond markets, and force a major reengineering of supply chains.

The end goal of fair and open trade is worth pursuing, and dismantling non-tariff barriers are a critical element in negotiations. It will be hard work, to be sure. The clock is ticking.

Read the full article here