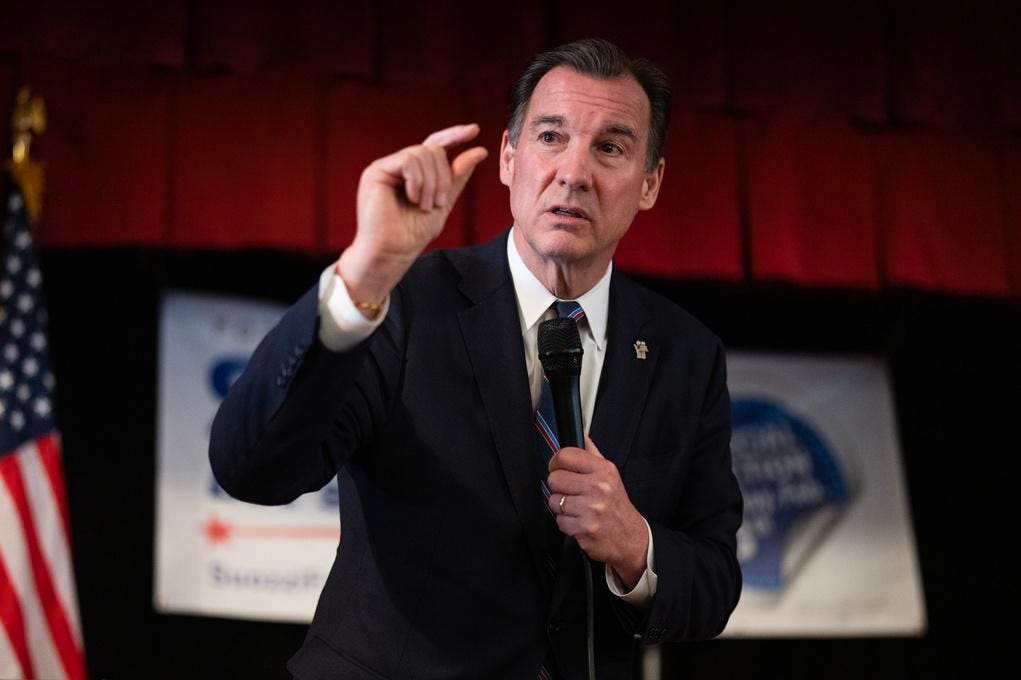

Rep. Tom Suozzi (D-NY) is exploring ways to lower the costs of his proposal for a public catastrophic long-term care insurance program. Among the ideas on the table: Simplifying the benefit structure and switching from a cash benefit to one that reimburses people for their out-of-pocket expenses.

Suozzi’s bill, the Well-Being Insurance for Seniors to be at Home (WISH) Act, would provide a lifetime long-term care benefit for people who need assistance with two of six daily activities, such as bathing, eating, dressing, and toileting.

Once somebody requires help with these tasks, they’d receive a benefit equal to the median cost of 6 hours of personal care a day, though they could use the benefit for a wide range of services. One study estimates the monthly value of this benefit at about $3,600, though it likely would be higher given recent increases in the cost of hiring care workers.

Participation in WISH would be mandatory and the benefit would be available to anyone after age 65 who works at least 10 years (similar to Social Security’s old age benefit).

Limiting Costs

But, according to a recent estimate from the Department of Health and Human Services, the original bill could cost substantially more than Suozzi expected.

When Suozzi originally introduced his bill in 2021, the benefit was funded with a 0.6 percent payroll tax, roughly $350 a year for a median income worker. He introduced a revised version in March, with two big changes. He gained a Republican cosponsor, Rep. John Moolenaar (R-MI), and he dropped the funding mechanism, with an understanding that some future source of revenue would fully finance the benefit without adding to the federal budget deficit.

But however it is funded, a 2024 Department of Health and Human Services estimate concluded that the original WISH Act would cost substantially more than Suozzi projected.

While the authors of that study acknowledged their estimate was highly uncertain, Suozzi and Moolenaar are searching for ways to reduce the cost and make the measure more acceptable to fellow lawmakers. Suozzi described the possible changes at a May 7 conference sponsored by the long-term care insurance company Genworth.

Reimbursement, Not Cash

The first revision would switch from a cash benefit to a reimbursement model, which is consistent with private long-term care insurance. However, such a change requires some important trade offs.

Cash gives recipients maximum choice in how they want to use the benefit. For example, they could use it to pay a neighbor for sitting with a frail parent or picking up her groceries, or pay for installing grab bars in a bathroom. There would be no need for complicated rules to describe what services and supports are reimbursable and what are not.

A cash benefit would lower administrative costs. But actuaries believe it significantly increases claims costs, in part because people usually will take their full daily cash benefit, while they often spend less on their actual services.

Suozzi can learn from the experiences of other countries that have public long-term care insurance programs. Some, such as Germany, offer a choice: a higher reimbursement benefit or a lower cash version. France provides a cash benefit only. Japan has only a service benefit.

A New Deductible Formula

The second revision Suozzi is considering would simplify how the benefit is calculated. Because his bill provides only catastrophic coverage, everyone would be responsible for paying for some care on their own before tapping the public benefit. The concept is similar to a health care deductible or, in the language of long-term care, an elimination period.

The original WISH Act set five different elimination periods of one to five years, based on an individual’s lifetime income. Those with the lowest incomes would be responsible for their first year of care while those in the highest income group would pay for the first five years before the public benefit kicks in.

The new design would shrink those tiers to just two. While the revised structure is still being considered, it could require the lowest-income half of the population to cover, say, the first 18 months of care on their own, while those in the top half might be required to pay for 2.5 years.

This revised format could both make the program easier for consumers to understand and save money. But some lower income people could end up paying more than under the earlier version, depending on the final design.

Many details of the WISH Act still need to be worked out, including both the final benefit structure and a source of revenue to finance the program over the long run. But WISH is an opportunity to address the difficult challenges of financing long-term care, which is beyond the abilities of most Americans and, at the same time, reduce Medicaid’s long-term care costs.

(Full disclosure: I serve as an upaid member of a WISH advisory group).

Read the full article here