This is news – or not.

Patagonia just sued a retailer in Maine for selling fakes. Last month, it was Lululemon.

Counterfeit alcohol is being blamed for deaths from Fiji to Türkiye. The U.K. issued a national alert last fall for potentially fatal fake booze.

ABC News in Chicago is reporting fake car seats. Earlier this month, there were reports of fake skin cream and Sharpie markers in Pennsylvania.

If you tell the average law-abiding citizens that they are buying illegal products, they probably will stop buying them, right?

Wrong, as we all know.

If buyers understood that every time they spent money for counterfeit handbags, they were not just creating work for low-income street vendors or flea market operators, but were shuttling their money to illegal operations, they would stop on a dime, right?

Wrong again.

These are the world’s worst terrorist organizations – those names you see on the news and watchlists – the people who have forced our society into accepting search wands, metal detectors, and long entry lines just to watch a football game or hear a concert. Surely, you’d never want to send even a nickel to the organizations which have necessitated this level of public security. (People who were born before around 1990 will remember that “airport-style” security was once only for airports.)

What does it say about consumers that they are anxious to buy counterfeit handbags or watches, even if they know that some of the people who profit the most are the people most of society reviles? Even while counterfeit products fund terrorism, consumers buy them, and buy for a lot of reasons.

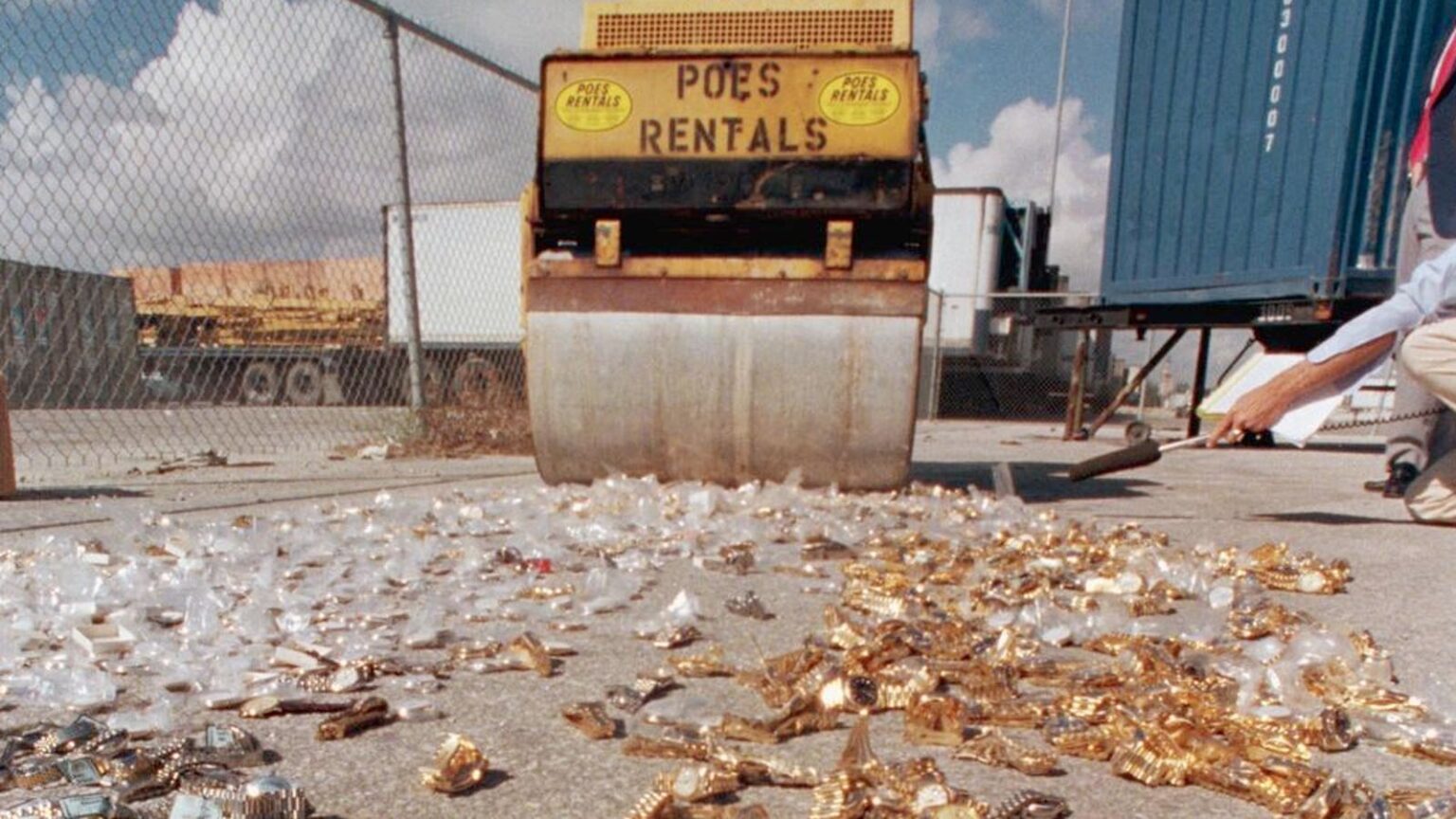

Two kinds of products regularly associated with counterfeits are handbags and luxury watches.

Having spent the last several decades searching out and trying to stop these products, I can tell you that although the landscape is very different now from previous times, some fundamental things stay the same.

A lot of consumers love having a prestigious brand name under their shoulder, and may desperately want to believe that there’s nothing wrong with fakes. Calling them “dupes” does not change the calculus. Some people love the idea that they think that when they buy knockoffs, they are somehow preventing big, powerful, wealthy giants from making money. They also may want to believe that what they’re buying are really identical goods that have just come out of the factory’s back door instead of the front, or that have fallen off the truck. Some want to believe that genuine luxury goods are no better than the mass market goods, so fakes and the real thing are identical.

Consumers may delude themselves into believing the profit margin of luxury brands, notwithstanding all of the other ordinary market risks and fluctuations, are disproportionately higher than the profits of other companies in other industries, because the street wisdom is legendary that luxury products must be generating profits of 1,000%.

Most of the dominant luxury brands in the world are owned by publicly held companies. Balance sheets are seen by the markets, and while they are profitable and sometimes intensely profitable, they are businesses like any other business, but they are not regularly profiting in the thousands of percent.

You get what you pay for. You can reject the idea of spending thousands of dollars for your handbag because you could easily buy one for $20, but that does not prove that the consumer isn’t getting fair value from luxury brands.

Trying to soften the criminal image of luxury counterfeits by using terms like “knockoffs,” “dupes,” or “replicas” does not change the facts. Other products like pharmaceuticals or industrial products, which can pose a literal threat to life and limb, don’t receive the same pass from consumers. Even non-ingestible consumer goods with no obvious health or safety implications may make consumers unwittingly (or willfully blindly) support the use of highly anti-sustainable materials that the consumers would reject in many of their other purchases.

But with luxury counterfeits, satisfaction is measured on a different scale.

Many consumers of counterfeit products aspire to an image – full stop. Those consumers who buy genuine luxury products believe those goods to be different, superior, and a fair value for the money they pay. Luxury goods manufacturers are also trying to attract customers based on the quality of the products on which they use their venerable brands.

The counterfeit issue is substantial through all strata of consumer markets. Counterfeit auto parts might leave one on the side of the road. Or worse. Many other knockoff products, like counterfeit pharmaceuticals, kill people. In some countries, poor populations rely on dispensaries to buy their pharmaceuticals literally one pill at a time (when one pill is all the patient’s budget will allow). The lack of control over labeling and distribution in these situations is notorious. Well-regulated brands provide a real defense against this.

But for all of that, people still don’t want to hear bad news.

The only way to try to make a dent in the sale of counterfeits is to follow the mantra of the New York Mets way back in the early 1970s – “You Gotta Believe.” Few people are really ready to believe their purchase of a fake watch for fifty bucks is anything more than a victimless crime, despite the vast dollars those sales generate for the bad guys. The U.N. tells us that fake luxury goods sales exceed auto parts and pharmaceutical sales.

The number of consumers who don’t Gotta Believe make life more dangerous.

Read the full article here